Alright, I’m bad at being timely. But in my defense, I got married! Twice! (well the second time was a “renewal” of the vows). But I have been thinking about this month’s topic – environmental flows – for a long time, largely because of the streamflow rules in the Columbia River Basin, where my research has focused for the last couple of years.

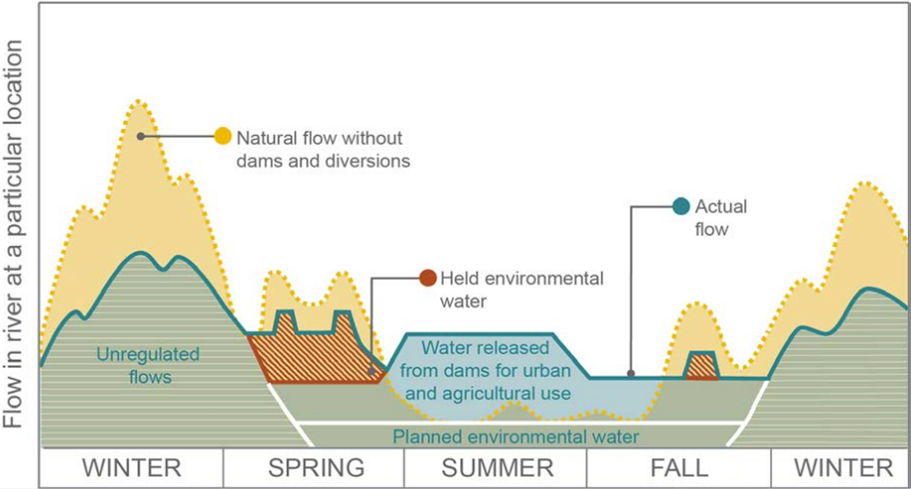

First things first though – what are* environmental flows? Water in rivers has myriad uses – irrigation for crops, recreation (swimming!), hydropower, and more. But, it is also there for non-humans. There are large, and important, ecosystems that exist in rivers and lakes, with aquatic life relying on minimum levels of water as well as a minimum quality of water. Plus, consider the surrounding vegetation (which needs water) and terrestrial animals that may rely on the water as well to drink, cool off, or hunt (looking at you bears). Really, what environmental flows boil down to is the consideration that streamflow had a pattern before humans, and the native ecosystem developed in response to and in conjunction with this pattern; we are the ones altering the levels of streamflow with dams (regulating and stabilizing river flows) and consumption of water. In California, for example, there are thousands of dams that impact river flow.

One of the most famous examples of environmental flow rules can be found in the state of Victoria, Australia. In 1989, the Water Act established that the environment has as much right to water as agriculture (irrigation) or people (drinking water) and subsequent amendments established actual environmental water entitlements (2005) and an entity to hold water rights on behalf of the environment (2010).

Do flow rules work?

Well… they are often not listened to. In the MDB, outcry from irrigators influenced implementation and size of the flow rules. Add to that a changing climate, which impacts water availability and seasonality, and it the view looks less than rosy. But, legislation with teeth (consequences) and with mechanisms to adapt to an uncertain future can still have the intended effect.

This legislation was part of the broader reform to manage water scarcity, with special regards to the interstate Murray-Darling Basin (MDB). Consequently, the environment is guaranteed a minimum of 2,750 gigaliters annually, to be shared between the riparian states.

But maybe you think that there are better uses for (and owners of) water in rivers than nature – after all, in sheer economic terms we should allocate water to its highest value use, and we value it very much. And, as I mentioned in my last post, environmental flows can account for more than 50% of water allocations. Should we really be allocating that much water to the environment when we don’t even know whether the fish that we are trying to help will survive the next 50 years?

That’s the argument some people make, but it doesn’t hold up when you consider all of the added benefits to keeping water in rivers “for fish”. First off, there are a lot of benefits to those fish – including tourism and food (I do love a good side of salmon). In Colorado, water-related recreation is estimated to contribute over $10 billion to state GDP annually. Then there are impacts broader ecosystems like wetlands and estuaries have on human life. For example, researchers have estimated that wetlands prevented an extra $625 million in flood damages Hurricane Sandy.

In the Columbia River Basin (CRB), environmental flows are most closely associated with salmon, which swim upriver each year to spawn. Salmon are integral to the river ecosystem. They carry nutrients from the ocean through rivers (yes, fish poop too); provide food for humans and animals alike; contribute nutrients to river systems when they die after spawning; are a critical part of local indigenous cultures; and draw tourists and fishers to towns along the rivers in the CRB. Increased streamflow provide – obviously – water for salmon to swim in, but higher streamflow** also translates to higher dissolved oxygen concentration (good for fish) and cooler temperatures (also good for fish – see nifty article on impacts of climate change).

One type of environmental flow: pulse flows

In 2014, about 1% of annual Colorado River flow was released into the river delta over the course of 8 weeks. This “pulse” flow was a short-term, temporary release meant to reinvigorate the river ecosystem. And it worked! Pulse flows – which are different from minimum flow requirements – are mimic seasonal flow periods and floods, which can serve as triggers for plants to bloom or key periods to spread seeds. Pulse flows can attract wildlife back to an area and, with limited releases, improve the natural habitat.

The Endangered Species Act of 1973(ESA) underpins regulation of actions that impact wildlife, fauna and flora alike, with the intent to protect threatened species (to state the obvious). As a result of the ESA, which I must emphasize is very complex, management of the CRB waterways has come under scrutiny with regards to its impact on salmon. In response to ESA protections, organizations like NOAA Fisheries issue Biological Opinions (also known as BiOp rules), which provide guidelines for how to meet the ESA, which end up impacting all users of water.

This was more an explanation than a hot take. But hopefully if you thought it was silly to give the environment a right to water, I have at least made you think more about it. Environmental flows have huge impacts on people and the economy – we may want to use the water today, but keeping it in rivers helps us in the long-term.

Now, I’m still behind on sleep and, worse, work, plus my perfectionist instincts have already kept me from posting this for one month, so I am going to have to cut this short. This is only a part I though, because though we have described environmental flow rules, there are discussion-worthy consequences, especially for hydropower producers like the one I study! So with this, bonsoir and hopefully see you sooner rather than later.

* I was going to title this post “Who Gets What(er)” (get it, water? Wat(are)?), but my now husband told me that my pun was exceptionally bad. I, for one, am still chuckling

** Research suggests that there is also a point at which flows can be TOO high and actually reduce survival. That said, this is far less common than the alternative of low flows.

One thought on “Fish are Friends?”