Alright, I did the typical New Year’s thing of making a resolution and then dropping it approximately two months in… BUT HEY! I am trying again. Plus admittedly the entire month of March and almost the entire month of April have literally disappeared – frankly, I can barely remember what I did, but it included a lot of trips up and down the east coast for wedding planning. But on to the day’s topic – prompted by the war in Ukraine: water wars.

If you have not heard, water resources have been a target in the war. Dams have been targeted, some successfully and others not, and the blockade of Mariupol included cutting off water supplies. Pres. Zelensky commented on the tragic consequences: “Listen to me carefully: In 2022, a child died from dehydration.” There was another water-related move though. In late February Russia announced that a canal blockaded by Ukraine during the annexation of Crimea was captured. For context, Russia actually brought a case to the European Court of Human Rights about access to water being blocked in 2021, while parties on the Ukrainian side accused Russia of creating the crisis. Now, the war in Ukraine is about far more than water getting to Crimea, and water has been more of a means than an end, but maybe addressing the topic years ago could have enabled conversation between the two parties more broadly.

But let’s zoom out a minute to these so-called water wars. First, I think that is a misnomer. I would call most water-related conflicts just that – conflicts – or even just tensions, far less buzzy than “water wars”. Even more disappointingly, I would characterize any incidents as conflicts involving water, as water is a secondary consideration or impact. Plus, the word “war” makes us think of international conflict, which is usually not the case; water is a very local issue, and conflicts sprout up domestically. Given this fine print and caveating (I really am becoming an academic), I will say that we see these tensions around the world, from the US to the Middle East to Bolivia.

Water scarcity.

Anyone who has taken an economics course should be able to tell you that the field is all about the allocation of scarce resources. But what makes something, like water, scarce? It’s when demand for water exceeds supply. There may be very little water in the desert, but unless there are humans who need it, we might not call it “scarce” – there is sufficient water for the organisms that have evolved there. Conversely, we might be in the wettest place in the world, but put enough industry and water demanding people there, and we might still find ourselves in a situation of water “scarcity”. All this to say – it’s sort of subjective.

Water use: consumption or withdrawal?

There are actually two different types of water use. The first, consumption, is use of water in a way that does not return to its source at all. For example – bottling water at a spring that will then be sold to people hundreds of miles away. The water may return to the environment, but it won’t return to the same basin. Evaporation, or transpiration by plants, are other forms of consumption.

Then there are water withdrawals. That means that the water is diverted from its source, but will return to it at some point. Think of your toilet flushing – you needed to withdraw the water to fill the toilet, but then it will get treated and released back into a local water source.

The distinction is important because if you are just withdrawing water, downstream users still have access to it (though you may get into the water quality issues). If you are consuming water, that prevents other users from accessing it.

In the US, we can think of the West/Southwest; anyone who lives or has lived in those regions is familiar with drought restrictions on water use. They could probably also tell you that it can be a tug-of-war between municipalities and agricultural users, which in California use about 10% and 40% of the water respectively. If you are good at math, you have also realized that only adds up to 50%. That’s right – the remaining half gets allocated for environmental flows (totally non–controversial as you might imagine –kidding if it wasn’t obvious). Side note: environmental flows are a topic so interesting they may deserve their own post in the future… And that’s the allocation in broad strokes. Don’t forget that the interests are far more wide-ranging: hydropower, power cooling, drinking water, irrigation, salmon runs, recreation/tourism…

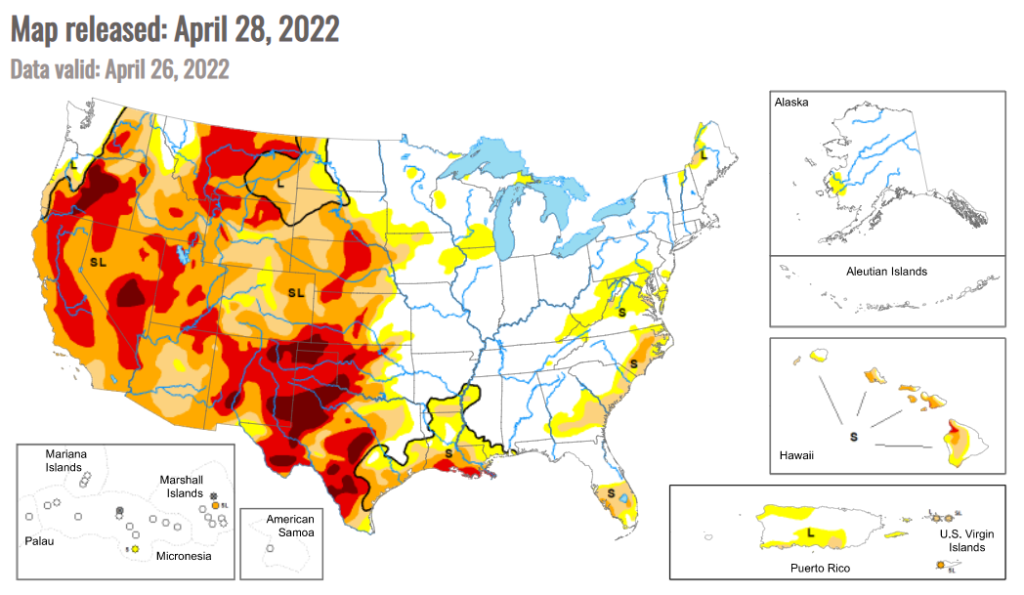

US drought monitor for the end of April 2022. The US West, for another year, is very, very dry.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is also often the poster child for water stress. My study abroad experience confirms this impression; there truly is little water compared to a lot of people and agriculture. The Syrian conflict infamously involved water. In Dr. Marwa Daoudy’s paper on the conflict – shout to Georgetown!! – she describes the continuous strategic use of water resources by both the Ba’athist government, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party, and ISIS for control of different populations and regions. These actions included flooding, cutting off water, and targeting infrastructure like pumping stations and dams. Again – an example less of traditional war between two states over a resource, but use of water as a means within much broader conflict. And I would be remiss if I did not mention Ethiopia (yes yes, sub-Saharan Africa, not MENA). The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), which Ethiopia has been building and now filling on the primary tributary to the Nile River – the Blue Nile – has caused massive tension with Egypt, with Pres. el-Sisi threatening “inconceivable instability” should the dam continue to be built. Plot twist, nothing has happened so far, at least with the dam.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, courtesy of Arab News.

There are many more examples, but I will highlight one of the most famous domestic cases: the Cochabamba water war. In 1998, water utility in Cochabamba, Bolivia was privatized at the best of the International Monetary Fund. The intent was to increase the financial sustainability of the water system but, as such, water prices skyrocketed. Naturally, this caused major issues – after all, a 50% increase in a water bill over two years is shocking for any household, and completely overwhelming for poorer ones. There were massive protests and by 2005 the private companies withdrew from Cochabamba. A word of caution – and a potential future topic – water pricing is a key component of sustainable water management. The situation in Cochabamba may have changed, but the issue of water supply and scarcity is as present as before.

The cherry on top of “water tensions” (yeah, I stand by my yawn-worthy phrase) is climate change – extreme weather events, like droughts, are expected to intensify and become more frequent in some regions. Combined with increased demands on the same water sources regardless of climate change (population growth! urban migration!), we can probably expect more water-related tensions in the future. Some attribute a non-trivial role in the Syrian conflict to climate change.

On the other hand, even if we have seen some conflicts involving water, we also had nearly 150 treaties governing water resources in the 20th century alone. One of my personal interests, the Jordan River, also highlights some cooperation between Jordan and Israel. Despite the many flaws and power asymmetries in the historical management of the river, there is something to be said for the two states’ longstanding relations.

So should we be focusing on water wars, or water tensions, or water whatevers? I think this article in the New Security Beat sums it up pretty well: if we double down on the narrative of water wars, we may generate them. In the case of Syria for example, other research suggests that there is no evidence for the role of drought in inducing civil war, despite much ado about it. Water governance is an incredibly complex issue; as my professor this semester frequently noted, we have “ancient instincts” around water. It should come as no surprise then that our water resources can become a casualty of bigger conflict. But let’s stay positive – it doesn’t look like water wars the way we imagined them are coming any time soon.

Featured image courtesy of the NY Times.

One thought on “Water Wars: all bark, or some bite?”